Boston-Alaska-Baja-Boston 2002

a trip report by Philip Greenspun

|

Boston-Alaska-Baja-Boston 2002a trip report by Philip Greenspun |

|

Just the facts:

Just the facts:

Itinerary:

Itinerary:

Our host was an expert seaplane pilot whom we'd met at the airport on

our first day in Anchorage. As we waited for the grill to warm up he

showed us his collection of 200 guns and some gold nuggets that he

kept for when the U.S. currency collapses. When asked how he'd

managed to get a machine gun license and learn how to use all of the

guns, he answered that he'd served in the Special Forces during the

Vietnam War. When he left the table to check on our 3"-thick steaks,

Kyle nervously whispered to me "I think he's going to kill us". I

laughed and said "Oh no, he's just an average guy for Alaska."

Our host was an expert seaplane pilot whom we'd met at the airport on

our first day in Anchorage. As we waited for the grill to warm up he

showed us his collection of 200 guns and some gold nuggets that he

kept for when the U.S. currency collapses. When asked how he'd

managed to get a machine gun license and learn how to use all of the

guns, he answered that he'd served in the Special Forces during the

Vietnam War. When he left the table to check on our 3"-thick steaks,

Kyle nervously whispered to me "I think he's going to kill us". I

laughed and said "Oh no, he's just an average guy for Alaska."

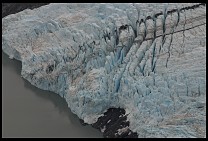

The treasures of Alaska include 6000'-high glacier-covered mountains right at the ocean's edge, endless tundra, old mining towns, bears fishing for salmon, a Massachusetts-sized region of 20,000'-high mountains cut through with low glacier-carved valleys. Almost all of this is inaccessible and invisible unless you're flying around in a small airplane. So that's what we did for six weeks (July 10 through August 25, 2002).

It is impossible to capture the experience of flying in Alaska with a

photograph. Up in a small airplane one is immersed in the landscape,

not looking at a small square image of scenery. It might be possible

to transmit some of the feeling by taking three high-resolution

panoramic images from the airplane. Image 1 would be of the sky;

Image 2 of the scene straight ahead; Image 3 of the ground below.

These images would then be printed 2 meters wide and wrapped around

the viewer in a hemisphere.

It is impossible to capture the experience of flying in Alaska with a

photograph. Up in a small airplane one is immersed in the landscape,

not looking at a small square image of scenery. It might be possible

to transmit some of the feeling by taking three high-resolution

panoramic images from the airplane. Image 1 would be of the sky;

Image 2 of the scene straight ahead; Image 3 of the ground below.

These images would then be printed 2 meters wide and wrapped around

the viewer in a hemisphere.

It is also pretty much impossible to capture the experience of being in wilderness Alaska with words and in this day and age of cheap air travel you might as well go and see for yourself. This letter to friends and family is just a random collection of thoughts and stories, many from the month that we spent getting to Alaska and the two months getting back to Boston (via Baja California). We covered most of the continent, making it from Kotzebue, just north of the Arctic Circle on the west coast of Alaska, to Cabo San Lucas, just south of the Tropic of Cancer at the tip of Baja.

Weather determines everything for the tourist in Alaska. Unusually

clear and calm weather enabled us to make a spectacular flight up the

Copper River Delta, 1000 or 2000' above the river and 5000' below the

mountain peaks on either side, to the old mining town of

McCarthy/Kennecott. Unusually windy weather trapped us on an island

in the middle of a lake in the middle of nowhere (Katmai National

Park) for two days. The wind howled through the tents. The

mosquitoes savaged anyone who ventured a few steps towards the island

interior. Rain came through periodically. There was nowhere to sit.

For two days we stared out at the whitecaps on the lake, back at our

rental kayaks with no spray skirts, and directly into the wind at our

destination on the other end of the lake. After two days we gave up

and kayaked downwind for 5 hours, looking over our shoulders at the

2-3' swell that threatened to swamp the little boats. Finally we

reached a camp where we could radio for a float plane to come in and

ferry us to the comparative civilization of Brooks Lodge. We took a

scheduled Penn Air flight back to Anchorage from King Salmon (our

little airplane was in the shop for a 100-hour inspection). The

flight attendant greeted our local friend Marion by name. They didn't

mind us carrying pocket knives on board (most of the other passengers

had guns) but there were a lot of signs relating to the proper

packaging of dead animal parts such as antlers.

Weather determines everything for the tourist in Alaska. Unusually

clear and calm weather enabled us to make a spectacular flight up the

Copper River Delta, 1000 or 2000' above the river and 5000' below the

mountain peaks on either side, to the old mining town of

McCarthy/Kennecott. Unusually windy weather trapped us on an island

in the middle of a lake in the middle of nowhere (Katmai National

Park) for two days. The wind howled through the tents. The

mosquitoes savaged anyone who ventured a few steps towards the island

interior. Rain came through periodically. There was nowhere to sit.

For two days we stared out at the whitecaps on the lake, back at our

rental kayaks with no spray skirts, and directly into the wind at our

destination on the other end of the lake. After two days we gave up

and kayaked downwind for 5 hours, looking over our shoulders at the

2-3' swell that threatened to swamp the little boats. Finally we

reached a camp where we could radio for a float plane to come in and

ferry us to the comparative civilization of Brooks Lodge. We took a

scheduled Penn Air flight back to Anchorage from King Salmon (our

little airplane was in the shop for a 100-hour inspection). The

flight attendant greeted our local friend Marion by name. They didn't

mind us carrying pocket knives on board (most of the other passengers

had guns) but there were a lot of signs relating to the proper

packaging of dead animal parts such as antlers.

Global warming has affected Alaska much more dramatically than the Lower 48. A couple of degrees of extra warmth have enabled the Spruce Beetle to thrive and destroy nearly every Spruce in south-central Alaska. We flew for hours over forests of dead brown trees. Changing ocean temperatures change where commercial fish species such as salmon can find food. Consequently towns that were once home to incredibly productive fishing fleets are now being deserted. In the old days when the catch was poor the prices were high. Today, however, farm-raised salmon keep the prices down even when the wild salmon are scarce. The increase in ocean height has been more dramatic here, leading to the inundation of Eskimo villages on gravel bars. One town, Shishmaref, is trying to get the state and federal government to pay $60 million to relocate its 250 inhabitants to higher ground.

Experiencing Eskimo culture was one of the highlights of the trip. It started with a six-hour flight from Anchorage to Nome. Alaska Airlines would have done this in two hours with little drama or fuss but for us it was a odyssey of climbing over a 10,000' mountain range, flying on instruments for two hours because the smoke was so thick from nearby forest fires, and then following a west coast of Alaska where it was at least 30 miles between manmade structures. The only ways in and out of Nome are airplane and ship (summer only; the ocean freezes in the winter). Once on the ground, however, there are rental cars and three gravel roads to explore, a total road network of 300 miles. One of these roads leads 50 miles from Nome, the white man's gold rush town, to Teller, an Eskimo village of 250 that happens to be the westernmost point on the North American continent to which one can drive on a public road. Almost anyone can manage to arrange food and shelter at the Equator. In the Arctic, however, every moment of life is purchased with human ingenuity. Maybe this is why Teller was the only place in North America that we visited that had wireless Internet connectivity (802.11b) spread over the entire town.

We did not encounter anyone in Alaska who sounded overworked or worried about his or her job. Nearly everyone either works for the government or in the booming tourist industry. State of Alaska workers get job security and many can retire after 20 years, e.g., school teachers. Federal workers get a 25 percent tax-free cost of living supplement, despite the fact that the actual cost of living in Alaska is substantially lower than in many parts of the Lower 48. You're not going to spend big bucks going out to fancy restaurants, Broadway shows, and the opera like a New Yorker. You're not going to pay $500,000 for a run-down 3-bedroom shack like a Californian. Milk is going to set you back but how much milk can you drink? There is no state sales tax and no income tax. In fact, every year the state of Alaska pays each Alaskan roughly $1500 per year from the Permanent Fund, a $22 billion collection of investments established with fees collected from companies extracting oil within the state. We heard about one family with 17 children. Every year they would get between $30,000 and $40,000 from the state!

Despite the high level of abundance on average, it is tough to become obscenely wealthy in Alaska; there is no Wall Street in Anchorage, no GE headquartered in Fairbanks. And even if you are rich it is impossible to become a feudal baron, Lower 48-style. No matter how fancy your private jet is, you could easily be grounded for a week or more by bad weather. No matter how big your mansion it could still be swept away by a tidal wave or shaken to rubble by an earthquake. A moose could walk in front of your chauffeured Mercedes. A bear could decide to come into your 100-acre backyard and make a meal out of you.

Despite the fact that it is impossible to have a realistic dream of ascending into the ranks of the tycoons, Alaskans seem content. Most Alaskans choose to live in Alaska because they love outdoor recreation and, with a modicum of education, it is relatively easy to earn enough to support a comfortable lifestyle enriched with hiking, biking, fishing, hunting, skiing, etc.

Contributing to the sunny mood of employed Alaskans is the nature of industry there. We visited a lot of big companies in the Lower 48 on the way to and from Alaska, companies such as Pixar and Winnebago. The architecture and mood inside their facilities made it clear that the arbeiters wouldn't be likely to keep their jobs if any of them started having their own opinions. But in Alaska even the largest government offices are fairly small and personal by Lower 48 standards. An FAA worker can't be fired for talking about the pinheads back in the main office in Washington. If the flight service woman is giving accurate weather briefings she need not fear discipline for expressing her opinion about the Saudis requesting (and receiving) all-male air traffic control for Prince Abdullah's airplane trip through Texas in the spring of 2002. Private employers in theory could exercise more mind control but in practice the offices are so small that oftentimes people are working without supervision.

Our darkest time in Alaska was traveling through the southeast coast,

from Juneau down to Ketchikan. This is where the cruise ships ply

their trade and they do all the brochure photography on sunny days.

Lush green mountainsides surround a flat sea punctuated by a breaching

whale. During our 10-day visit in August it was much more common to

strain one's eyes through the driving rain to see clouds hanging at

300' off the mountainsides. We'd go out to the airport to fetch

something from the airplane and learn that Alaska Airlines had not

been able to get in for 24 hours. Flying from island to island was

terrifying and being on the ground was miserable. Most of the towns

in Southeast have only one hotel or restaurant and there is virtually

nothing to do indoors. Kyle's mom and our friend Richard had joined

us for this leg of the trip and the four of us huddled inside the 150

square foot Winnebago.

Our darkest time in Alaska was traveling through the southeast coast,

from Juneau down to Ketchikan. This is where the cruise ships ply

their trade and they do all the brochure photography on sunny days.

Lush green mountainsides surround a flat sea punctuated by a breaching

whale. During our 10-day visit in August it was much more common to

strain one's eyes through the driving rain to see clouds hanging at

300' off the mountainsides. We'd go out to the airport to fetch

something from the airplane and learn that Alaska Airlines had not

been able to get in for 24 hours. Flying from island to island was

terrifying and being on the ground was miserable. Most of the towns

in Southeast have only one hotel or restaurant and there is virtually

nothing to do indoors. Kyle's mom and our friend Richard had joined

us for this leg of the trip and the four of us huddled inside the 150

square foot Winnebago.

Kyle and her mom escaped by moving up their reservation for the Winnebago on the Alaska Marine Highway. Richard and I escaped by flying through the clouds to Prince Rupert, on the British Columbia coast, then inland up a narrow river valley through the 10,000'-high mountains. We were under the clouds for the first 50 miles and then broke out to a clear blue sky in interior B.C., our first in two weeks.

One thing that you learn from traveling 3000' above the ground is just

how mountainous western North America is. Roads are built in valleys.

When you drive on a road you see a mountain ridge on either side but

you have no idea what lies beyond those ridges. The viewpoint from an

airplane flying above the road is of mountain after mountain receding

to the horizon. The structure of geography is more apparent from the

air. You see the glaciers on top of the mountains. You see the

waterfalls on the mountainsides where the glaciers are melting. You

see the rivers carrying the meltwater through the valleys. You see

the smaller rivers combining into one big river. You see the big river

emptying into the ocean.

One thing that you learn from traveling 3000' above the ground is just

how mountainous western North America is. Roads are built in valleys.

When you drive on a road you see a mountain ridge on either side but

you have no idea what lies beyond those ridges. The viewpoint from an

airplane flying above the road is of mountain after mountain receding

to the horizon. The structure of geography is more apparent from the

air. You see the glaciers on top of the mountains. You see the

waterfalls on the mountainsides where the glaciers are melting. You

see the rivers carrying the meltwater through the valleys. You see

the smaller rivers combining into one big river. You see the big river

emptying into the ocean.

The world of human artifacts looks very different from the air as well. Cobblestone streets lined with quaint and charming houses aren't very interesting from the air because they are simply too small. An Aluminum smelter, however, will pique one's curiosity and prompt a 10-mile detour. America turns out to be a land of paper mills, truck factories, sewage treatment plants, mines, quarries, etc. These are seldom seen by a motorist because they are far off the main roads and hidden behind forests.

Social and economy trends are apparent from the air. Old towns consist of a grid of streets, arranged fairly near some sort of wealth-generating industrial facility such as a mill. All of the houses are on this grid. Some streets have larger and fancier houses but everyone in the town lived more or less in the same way and people from different income strata rubbed shoulders at least occasionally.

New housing is set without reference to any obvious-from-the-air source of jobs. People who leave these houses to go to work have a much longer commute than they did in the old days. Different economic classes are kept completely separate. The lower middle class live in mobile home parks, the roofs of the double-wides unmistakable from the air because there are seldom any trees. The modern middle class live in treeless exurban housing developments with a lot of cul-de-sacs. The dual-income yuppies live on farms that have been broken up into tall McMansions, each one resting on a small pad of grass with dwarf trees.

The separation that is started by class finishes with golf. The U.S. has 23,000 golf courses and they are seemingly everywhere. Small towns whose industry packed up and left 40 years ago have golf courses. The Sierra Club has made sure that you can't walk a dog--even on a leash--in Death Valley National Park but apparently it helps the environment to suck up all the underground water to feed a lush 18-hole golf course 214' below sea level. The growing cities of the West sprawl from new golf course to new golf course. Golf contributes to the fragmentation of society because all the new golf courses are wrapped around McMansions. People move to exurban developments in order to take a job, not because they're drawn to a community. Upon retirement there is no reason for them to stay so far from the thing that they cherish most: the golf course. Thus before a resident of Sprawltown, California has had a chance to get to know his neighbors, chances are you'll find him living on a fairway.

"Enlarge the place of your tent.. do not hold back"The rich are different, of course, and the 21st-century rich are different from the 1960s rich. In the 1950s a corporate executive's income was 5-10X that of the average worker and his mode of transport was the automobile. The executive's vacation house was thus a cabin in the woods within a 2-3 hour drive of the main house. Today the executives at a big company are making 100-1000X the income of the average worker and their mode of transport is the company jet. The CEO, CFO, or SVP or whatever can be 1500 miles from the primary home within 3 hours, all at shareholder expense. The shareholder-paid-for jet (Enron reduced their fleet to 19 jets after they filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection) makes it possible for each executive to own 5 or 6 houses. These houses are highly visible from a small airplane because they're so big. Life begins at 10,000 square feet when you're on the Board of Directors. It must be said that architecturally these houses don't look so great. When you're building 5 or 6 huge houses and need to keep expenses under control the easiest method is to hire the same architects and construction firms that build Holiday Inn Expresses. If you see a Holiday Inn Express next to a Home Depot, you know that you're looking at a hotel. If you see a few Holiday Inn Expresses dotting a wooded lakeside you know that you're looking at an executive neighborhood.

-- Isaiah 54:2

Finally there are the megarich. Flying over the Hamptons or Napa Valley you can see the estates that are typically hidden behind high fences and mile-long driveways. Ira Rennert's house under construction in Southampton, Long Island is a good example. The complex is approximately 110,000 square feet including a 30-bedroom, 30-bathroom main house and will cost roughly $100 million (see Malcolm Gladwell's January 25, 1999 New Yorker article). The project is typical in that most people have never heard of Ira Rennert and that most of the money comes from financial engineering that siphoned money from ordinary investors into his own pocket (see the July 22, 2002 issue of Forbes).

Americans who formerly lived together have been torn apart by wide highways and cheap automobiles leaving only one thing to unify their modern structures: whether built for the rich or the poor, new buildings look ugly from the air. Old mills and churches look good from the ground and great from the air. Architects of new buildings have apparently decided that God isn't watching. The roofs of modern structures are bleak expanses of tar punctuated by air conditioners.

One thing that shocks most passengers is how friendly the U.S. is to aerial tourism. We took a bunch of people sightseeing from the Napa County airport, at the north edge of San Francisco Bay. We'd fly over San Quentin State Prison, Sausilito, and just above the towers of the Golden Gate Bridge. At this point we were 2000' above sea level and heading for downtown San Francisco. The passengers, whose brains had been marinated in images of angry Muslims flying big jets into downtown skyscrapers, would say "Aren't there rules that keep you from flying so close to these buildings?" We'd be right over the Transamerica pyramid at this point in the conversation. "Oh no, in fact the FAA won't allow us to fly too far above our current altitude. There aren't any special rules for big cities. You just need to be 1000' above the buildings in a congested area and 500' above buildings in a rural area. The airspace that is carefully controlled is that around major airports--the FAA doesn't want us to collide with a passenger jet. So we're not allowed near SFO or in the higher rings where big jets might be coming down or climbing out." That issue settled, we continued over the Bay Bridge, the Berkeley Campus, the big oil refinery in Richmond, and some mothballed Navy ships before returning to land at Napa.

We grew to love Canada. The authors of A Pattern

Language say that the optimum size for a country is 2 to 10

million people. If a nation grows larger the government will become

too remote from the citizens. To that we might add that if a country

of immigrants becomes too densely populated the citizens will begin to

get on on anothers' nerves. In the U.S. the symptoms of people

irritating each other are most apparent on the West Coast. Americans

moved to California expecting to have a great time. If they aren't

having a great time they begin to pass laws hoping to ensure that they

enjoy the lifestyle that they deserve: communities where kids are

forbidden, downtown streets where it is illegal to walk a dog or smoke

a cigarette, restrictions on bicycling. In the redwood forests of

northern California humans have cut down 96 percent of the old trees

and are continuing to cut more all the time (it will take 700 years to

replace the redwoods and probably they won't regrow due to global

warming). What are the state and federal governments doing about

this? Putting up "no dogs" (not even leashed) signs on every trail.

They also keep improving high-speed truck highways through the forests

but there are no bike lanes, bike trails, or plans to build any.

We grew to love Canada. The authors of A Pattern

Language say that the optimum size for a country is 2 to 10

million people. If a nation grows larger the government will become

too remote from the citizens. To that we might add that if a country

of immigrants becomes too densely populated the citizens will begin to

get on on anothers' nerves. In the U.S. the symptoms of people

irritating each other are most apparent on the West Coast. Americans

moved to California expecting to have a great time. If they aren't

having a great time they begin to pass laws hoping to ensure that they

enjoy the lifestyle that they deserve: communities where kids are

forbidden, downtown streets where it is illegal to walk a dog or smoke

a cigarette, restrictions on bicycling. In the redwood forests of

northern California humans have cut down 96 percent of the old trees

and are continuing to cut more all the time (it will take 700 years to

replace the redwoods and probably they won't regrow due to global

warming). What are the state and federal governments doing about

this? Putting up "no dogs" (not even leashed) signs on every trail.

They also keep improving high-speed truck highways through the forests

but there are no bike lanes, bike trails, or plans to build any.

With 31 million people, Canada is a bit larger than the Pattern

Language suggests is optimum. Nonetheless, when you get to a

Canadian park you're handed a brochure outlining the most pleasant

trails for mountain biking and asking that bikers be considerate of

other trail users. It is easy to find dog-friendly hotels all across

Canada. And generally Canadians are extremely polite and

well-educated. Despite their frigid climate, Canadians can expect to

live two years longer than Americans. "Although America has higher

per capita income than other advanced countries, it turns out that

that's mainly because our rich are much richer," notes Paul Krugman in

the October 20, 2002 New York Times Magazine (http://www.pkarchive.org/economy/ForRicher.html).

Indeed in wandering around Canada one seldom seems a $120,000 Mercedes

but the average person seems as well off as (and more relaxed than)

his or her American counterpart.

With 31 million people, Canada is a bit larger than the Pattern

Language suggests is optimum. Nonetheless, when you get to a

Canadian park you're handed a brochure outlining the most pleasant

trails for mountain biking and asking that bikers be considerate of

other trail users. It is easy to find dog-friendly hotels all across

Canada. And generally Canadians are extremely polite and

well-educated. Despite their frigid climate, Canadians can expect to

live two years longer than Americans. "Although America has higher

per capita income than other advanced countries, it turns out that

that's mainly because our rich are much richer," notes Paul Krugman in

the October 20, 2002 New York Times Magazine (http://www.pkarchive.org/economy/ForRicher.html).

Indeed in wandering around Canada one seldom seems a $120,000 Mercedes

but the average person seems as well off as (and more relaxed than)

his or her American counterpart.

[Note that if small is beautiful and the Pattern Language authors are correct, it is tough to understand why nobody ever questions the U.S. goal of rebuilding Afghanistan as one country. The 2-10 million number was for countries with universal literacy, a common language, pervasive mass media, excellent road networks, etc. Afghanistan has 25 million people (despite some reportage about starving children the population is growing at one of the fastest rates of any country in the world). More than two thirds of Afghanis are illiterate. It is virtually impossible for these folks to travel from one part of the country to another and if they did they'd discover that they had nothing in common because there are 3 major and 30 minor languages spoken by the various ethnic groups who are further divided into mutually antagonistic Shi'a and Sunni sects of Islam. If Northern and Southern California are always talking about splitting up you'd think that we would hear some discussion of splitting up Afghanistan into 4 or 5 countries, in each of which the citizens can talk to each other in a common language, can visit each other in less than a week of travel, and don't dislike each other for religious or ethnic reasons.]

|

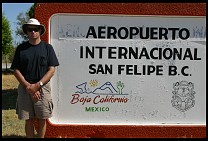

Bringing your own airplane into Mexico shelters you from the

border-town horrors that are so familiar to motorists. Our first stop

was San Felipe, a 4- to 6-hour drive from the population centers of

Southern California and a full 2.5 hours south of the U.S. border.

Upon taxiing up to the sleepy terminal we are met by three soldiers

carrying rifles. They poke around a bit in the back of the airplane,

ask us (in English) whether we had any guns or drugs, look at our

documents, and return to their shed. A team of pleasant

English-speaking officials swings into action to walk us and our

airplane through the bureaucracy. The air traffic controller comes

down from the tower to admire our Diamond Star--it seems that he is

taking flying lessons in a beat-up old Cessna. Every now and then he

pauses to use his handheld radio to respond to calls from an incoming

American pilot. When that pilot finally lands, they greet each other

by name. We buy some high-octane aviation gas and continue down the

Sea of Cortez coast. Total time on the ground: 30 minutes.

Bringing your own airplane into Mexico shelters you from the

border-town horrors that are so familiar to motorists. Our first stop

was San Felipe, a 4- to 6-hour drive from the population centers of

Southern California and a full 2.5 hours south of the U.S. border.

Upon taxiing up to the sleepy terminal we are met by three soldiers

carrying rifles. They poke around a bit in the back of the airplane,

ask us (in English) whether we had any guns or drugs, look at our

documents, and return to their shed. A team of pleasant

English-speaking officials swings into action to walk us and our

airplane through the bureaucracy. The air traffic controller comes

down from the tower to admire our Diamond Star--it seems that he is

taking flying lessons in a beat-up old Cessna. Every now and then he

pauses to use his handheld radio to respond to calls from an incoming

American pilot. When that pilot finally lands, they greet each other

by name. We buy some high-octane aviation gas and continue down the

Sea of Cortez coast. Total time on the ground: 30 minutes.

The east coast of Baja looks a lot like the Grand Canyon: a 5000'-high

ride of eroded sandstone. What is different from the Grand Canyon is

that there is a white sand beach in front of the beautiful mesas.

Every now and then one flies over a mine or a handful of beach houses

that sprout when a road touches the coastline but otherwise the place

seems deserted. Having departed San Diego at 9:00 am, we shut down at

4:00 pm in the quiet town of Loreto, population 10,000. One of the

advantages of Mexican aviation being so bureaucratic is that there is

always an official around when you need local advice. The flight

planner in Loreto directed us to a fine courtyard hotel ($32) in the

center of the 300-year-old town from which we could walk to the

mission, stroll along the seafront (a German couple was picnicing on a

bench despite a 15 mph wind directly in their faces), and shop for

Diet Coke and ice cream. Citizens of Loreto don't seem rich but

nobody seems all that poor either and certainly there are no beggars,

which is a big change from the cities of the U.S. Pacific coast. We

met an American couple at the mission museum and joined them for

dinner. They exemplified the "work to live" Norteamericanos who come

down to Baja for extended periods of time. These two would work just

long enough in southern California to provision their sailboat, then

spend 6-10 months sailing around the Sea of Cortez and the west coast

of mainland Mexico.

The east coast of Baja looks a lot like the Grand Canyon: a 5000'-high

ride of eroded sandstone. What is different from the Grand Canyon is

that there is a white sand beach in front of the beautiful mesas.

Every now and then one flies over a mine or a handful of beach houses

that sprout when a road touches the coastline but otherwise the place

seems deserted. Having departed San Diego at 9:00 am, we shut down at

4:00 pm in the quiet town of Loreto, population 10,000. One of the

advantages of Mexican aviation being so bureaucratic is that there is

always an official around when you need local advice. The flight

planner in Loreto directed us to a fine courtyard hotel ($32) in the

center of the 300-year-old town from which we could walk to the

mission, stroll along the seafront (a German couple was picnicing on a

bench despite a 15 mph wind directly in their faces), and shop for

Diet Coke and ice cream. Citizens of Loreto don't seem rich but

nobody seems all that poor either and certainly there are no beggars,

which is a big change from the cities of the U.S. Pacific coast. We

met an American couple at the mission museum and joined them for

dinner. They exemplified the "work to live" Norteamericanos who come

down to Baja for extended periods of time. These two would work just

long enough in southern California to provision their sailboat, then

spend 6-10 months sailing around the Sea of Cortez and the west coast

of mainland Mexico.

In the morning we hopped a cab to the airport and proceeded south to

Los Cabos International, rented a car and drove for an hour on coastal

dirt roads to visit some friends of Elsa Dorfman. We knew almost

nothing about them or the place except what Elsa had said: "they had a

commune in the 60s and have stuck together." It turns out that this

family (as they call themselves) of necessity taught themselves how to

build houses that were sufficiently large for 40 or 50 people to live.

They didn't have much money and they had 40 or 50 people. Then they

discovered that there were a handful of rich people who, though they

were basically alone, wanted to live in a house large enough for 40 or

50 people. Then through the 1980s and 1990s the rich in the

U.S. become so much richer that there were tens of thousands of

individuals with the means to afford a baronial lifestyle. Like any

American business catering to the superrich, the family's home

construction company prospered and some of the surplus was spent on a

5-house vacation villa on the coast in Baja. We were able to observe

some of the hardships of communal living. If you're a man you can't

imagine yourself absolute lord and master of the house. If you're a

parent you can't have the last word in how your children are going to

be educated. But in a world of ever-smaller families and families

fragmented by divorce there was something wondrous about living in a

family where more than 50 other members stood ready to lend support

through a crisis. In a world where family members gobble drive-thru

in the car on the way to their disparate activities it was nice to see

12 people sitting down together for three meals per day. We had a

group excursion up the coastal road to snorkel on the coral reef, then

back to a (dog-friendly) national park beach for a picnic. We sat in

the pool and waterfall when we could no longer take the heat. We went

back to the airport for sightseeing flights over the house and the

tourist hotels of Cabo San Lucas. They might never have gotten rid of

us if the villa had been on the power grid--adapting to life without

Google was tough and life without air conditioning was unthinkable.

In the morning we hopped a cab to the airport and proceeded south to

Los Cabos International, rented a car and drove for an hour on coastal

dirt roads to visit some friends of Elsa Dorfman. We knew almost

nothing about them or the place except what Elsa had said: "they had a

commune in the 60s and have stuck together." It turns out that this

family (as they call themselves) of necessity taught themselves how to

build houses that were sufficiently large for 40 or 50 people to live.

They didn't have much money and they had 40 or 50 people. Then they

discovered that there were a handful of rich people who, though they

were basically alone, wanted to live in a house large enough for 40 or

50 people. Then through the 1980s and 1990s the rich in the

U.S. become so much richer that there were tens of thousands of

individuals with the means to afford a baronial lifestyle. Like any

American business catering to the superrich, the family's home

construction company prospered and some of the surplus was spent on a

5-house vacation villa on the coast in Baja. We were able to observe

some of the hardships of communal living. If you're a man you can't

imagine yourself absolute lord and master of the house. If you're a

parent you can't have the last word in how your children are going to

be educated. But in a world of ever-smaller families and families

fragmented by divorce there was something wondrous about living in a

family where more than 50 other members stood ready to lend support

through a crisis. In a world where family members gobble drive-thru

in the car on the way to their disparate activities it was nice to see

12 people sitting down together for three meals per day. We had a

group excursion up the coastal road to snorkel on the coral reef, then

back to a (dog-friendly) national park beach for a picnic. We sat in

the pool and waterfall when we could no longer take the heat. We went

back to the airport for sightseeing flights over the house and the

tourist hotels of Cabo San Lucas. They might never have gotten rid of

us if the villa had been on the power grid--adapting to life without

Google was tough and life without air conditioning was unthinkable.

We experimented with the Cabo tourist scene by staying one night at the Hotel Westin Regina, whose cascading pools had looked so inviting from the air. The lobby was filled with Californians taking "The Wisdom", which is what you do with your vacation weeks after you've completed the Landmark Forum. They warned us about the $50 buffet dinners but not about the food poisoning that wouldn't let go of our stomachs for a full week (and even then required a course of the antibiotic Cipro).

We limped back to the airport and flew up to small riparian oasis of Mulegé, where the Hotel Serenidad has its own dirt-and-sand airstrip. The hotel also happens to be right on the main highway through Baja and we happened to share our swim-up bar stools with a group of offroad motorcyclists making their way down to Cabo on the side roads. "I love the kids here," one of the dirt bike heroes noted, "I gave one of them a peanut butter cup and, without pausing or saying anything, he broke it into six pieces and shared equally with his friends."

If it had not been for the airplane we would have gone through our entire trip without any substantive interactions with Mexican nationals. In navigating the Mexican aviation bureaucracy we ended up talking with at least 20 fluent English speakers. These folks are very well informed about current events and politics on both sides of the border but their direct experience of Americans is skewed by their general aviation jobs. The only Americans that they see day-to-day are corporate executives coming down to Baja for the weekend in the company jet and typical small airplane owner-pilots, 55-year-old guys with beer guts and a thirst for cheap tequila. "Your government confuses us," one official noted. "They spend so much money trying to keep Mexicans from coming over the border to work even though your economy couldn't survive without Mexican labor. Meanwhile they welcome Arab immigrants who hate the United States. What have the Muslims that you let in contributed to the American economy? Enough to pay for all the damage of September 11? I don't think so. But as soon as the World Trade Center dead are buried the U.S. government goes back to talking about its ally Saudi Arabia and preventing Mexicans from crossing the border or working legally." Fortunately the ill-will engendered by the U.S. government does not extend to American citizens personally. Mexicans have lived for generations with a self-perpetuating ruling class and they do not assume that the American politicians have the support of the average American.

We returned to the United States at Calexico, California, not far from where the Colorado River flows into Mexico, a sore point in U.S.-Mexican relations for more than 100 years. In the old days the Colorado flowed freely through the Grand Canyon and down the California/Arizona border and into Mexico where its water could be used for irrigating crops while its silt fertilized them. The U.S. began by building dams, notably the Hoover and Glen Canyon, to trap all the silt and most of the water. It was decided in a 1944 treaty that the Mexicans would have to content themselves with 10 percent of the flow; 90 percent would be consumed within the U.S. Starting in the 1960s, however, the U.S. government had sold off so much water at such low rates to farmers in Arizona that it was forced to return some of the irrigation water back to the water in order to live up to the "leave the Mexicans with 10 percent" treaty. While on its tour of American fields this water picked up a tremendous amount of salt to the point that by the 1960s the Colorado River in Mexico was saltier than the ocean. We were literally salting their fields! In 2002 the accusations are being hurled in the opposite direction; farmers in Texas are upset because the Mexicans are taking more than their agreed-upon share of the Rio Grande. The Colorado River situation is quieter but a bit sad. The Mexicans use their 10 percent to irrigate fields in Mexicali and that means the once-might Colorado dries up before it can reach the sea.

We visited every public aquarium in North America and the winner is... the Tennessee Aquarium in Chattanooga. Designed by the same architects that did most of the other aquaria in the U.S., Cambridge Seven Associates, this one has a cathedral-like feeling. You're inside a 12-story-high tower of fish, walking down ramps from the top, watching exhibits that follow the course of the Tennessee River from mountain stream beginnings to its terminus in the Gulf of Mexico. At all times you've got views up and down the dimly lit interior, which is crowned with a wavy fiber optic light sculpture. It cost $45 million to build, which is only a bit more than a lot of Fortune 500 executives are spending on their Greenwich, Connecticut manor houses. If we ever join the plutocracy this is how we want to live. We'll put a bed at the top of the first ramp and call that the master bedroom. We'll put a sofa at the bottom of the first ramp and call that a living room. A desk on the next landing down will turn it into an office. And there's already a big kitchen on the ground floor!

Our favorite artists' colony is Marfa, a dying West Texas town way off the Interstate that was turned around when minimalist artist Donald Judd purchased the National Guard armory, the supermarket, and all the other big buildings that he could find. These buildings have been turned into the world's largest permanent collection of installation art and the town is sort of where Santa Fe, New Mexico was 30 years ago. Most of the art was created in situ, i.e., the artist showed up in Marfa, looked at the building, and created the art to fit the space while simultaneously adapting the space to fit the art. Judd felt that art museums weren't serving installation art well, that the focus in a 20th century art museum was on the museum and its donors rather than the art. Judd is dead but his ideas live on at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa and with the artists who come to work in Marfa and hang out in the bookstore/wine bar.

[If Judd had lived into this century he might have noticed that the 21st century museum is really a tax-free club for the rich. The old style art museum is a civic center where the lower middle class can be uplifted by viewing great works. Think about New York City's Metropolitan Museum where a poor kid could donate a penny and then spend the entire day roaming the halls. In this context it is tough to understand the latest crop of American art museums, which feature a magnificent $50 million building, an undistinguished collection displayed in a handful of rooms, an admission price of more than $10, and most of the interior space geared for social gatherings. These museums are nearly empty during the daytime but they come alive at night for members-only events. What do we call a fancy building that contains a few paintings and is periodically filled with rich people sipping drinks and hors d'oeuvres? A private club. How would you like to deduct your club dues and not pay property tax on the building? Let's call it an art museum! What if the rabble try to get into our private club? Discourage them with a $12.50 admission fee.]

Taliesin, where the 4-hour tour is $70

Milwaukee Art Museum's $75 million Santiago Calatrava addition

|

Picking a favorite place to live is especially tough. We loved Spokane, Washington, perhaps because we visited in the sunny dry month of September. Spokane is uncrowded and friendly, blessed with lovely Olmsted-designed parks, and with just enough culture to bring people out of their (very affordable) houses. If you work in a hospital or state university in Spokane you'll get paid roughly the same as a medical or educational worker at a similar institution in, say, San Francisco. But your standard of living will be much higher because housing is so much cheaper. On the other hand the industrial economy of Spokane is flat on its back and if you aren't a medical doctor chances are that you'll be working at Starbucks. Houses are cheap but not quite cheap enough for the service worker. People who live in the crowded cities of the Pacific coast never seem to have any trouble finding jobs but there is so much money chasing so few houses that the prices of even modest dwellings are bid up to the stratosphere. In order to be able to afford the cost of living in, say, the Bay Area, people commute and work so many hours that they seldom have time to enjoy the cultural richness of the area and they certainly do not have time to engage in community-building volunteer organizations. We visited a friend living in a beautiful townhouse in San Francisco, not far from the Getty Mansion: "I'm thinking about moving to Italy. People here go to expensive restaurants every night for dinner but they don't really enjoy themselves or the food. They're always thinking about work." It is worse for the young. The poor ones we saw begging on the streets (something we did not see in Mexico!) and the rich ones have it tough as well, according to our friend: "My work puts me in contact with a lot of rich people. I ride around with them in their private jets and helicopters and visit their vacation houses. They aren't any happier than anyone else. The only real difference is their kids. Imagine working all summer on a paper route and saving $1000 only to see your parents spend $20,000 on a weekend getaway or in an afternoon of shopping. The children of the rich become demotivated, especially if their parents are famous as well as being rich, because they believe that nothing they can do themselves will matter compared to what their parents have done." From all of this we conclude that the most congenial places to live are those in which the average 40-hour-per-week job provides enough income to buy a decent house for a family. For incomes to be this high and real estate prices to be this low the place must have harsh enough weather to be unattractive to wealthy retirees (who would generate inflation in real estate), be sort of spread out so that real estate prices aren't bid up by scarcity of land, and have employers that can't export their jobs to low-wage countries (i.e., government and health care). Sounds like... Anchorage or most of Canada!

If you're young and strong enough to carry a week's worth of supplies

into the backcountry, almost any U.S. national park offers a

natural contrast to urban living. If physical ability or inclination

keeps you within a one-hour walk of a car, you might find yourself in an

environment more urbanized than many parts of Manhattan. As the number

of visitors to national parks has increased, the U.S. National Park

Service has steadily cut back on the permissible activities off the

paved road network. You can't walk a dog on a leash on a national park

trail, even in parks with no wildlife or vegetation. Mountain biking is

illegal. You can't ride a bicycle on the pavement in parks such as

Glacier because the Park Service has decided that it is too dangerous

and that cars should have priority (in other parks it is still legal to

ride a bike on the road but printed brochures discourage the practice).

Horse travel is prohibited in most areas. Small inns in isolated areas

of the parks are gradually disappearing. As the paved roads become

more congested the Park Service bans private automobiles. At the

Grand Canyon's south rim, for example, cars are banned from the rim

roads and overlooks, even in the off season. Visitors are supposed

to queue up at designated spots and get on a light rail system, sort of

like the New York City subway. Unfortunately there is no money to

build the light rail system so the park service uses noisy diesel buses

instead. The buses aren't accessible to those in wheelchairs,

however, so people in wheelchairs have to plan their activities one day

ahead of time in order to reserve an accessible shuttle. Overall

the number of visitors and vehicles coming into the park has doubled

since 1970 while the facilities at the rim have not grown. Even in

the harsh cold of mid-October, for example, all the hotel rooms and most

of the campsites were booked. The park follows the river for

nearly 300 miles and the rim is deserted for most of this distance,

although from the air one can see a network of dirt roads that afford

vehicle access. If the Park Service picked a spot 30 miles to the

west and developed some new hotels, the experience of visiting the park

would get back to where it was in 1970. But it isn't going to

happen so unless you're strong enough to hike while carrying two gallons

or water per person per day the only way to get away from the crowds is

to go to a national park in Canada or to visit one of the less popular

U.S. national parks. Our favorites for a mix of scenery, comfort,

and lack of crowds are the following: Death Valley (complete with

golf course and below-sea-level airport), Grand Teton, any of the parks

in Alaska, and Big Bend.

If you're young and strong enough to carry a week's worth of supplies

into the backcountry, almost any U.S. national park offers a

natural contrast to urban living. If physical ability or inclination

keeps you within a one-hour walk of a car, you might find yourself in an

environment more urbanized than many parts of Manhattan. As the number

of visitors to national parks has increased, the U.S. National Park

Service has steadily cut back on the permissible activities off the

paved road network. You can't walk a dog on a leash on a national park

trail, even in parks with no wildlife or vegetation. Mountain biking is

illegal. You can't ride a bicycle on the pavement in parks such as

Glacier because the Park Service has decided that it is too dangerous

and that cars should have priority (in other parks it is still legal to

ride a bike on the road but printed brochures discourage the practice).

Horse travel is prohibited in most areas. Small inns in isolated areas

of the parks are gradually disappearing. As the paved roads become

more congested the Park Service bans private automobiles. At the

Grand Canyon's south rim, for example, cars are banned from the rim

roads and overlooks, even in the off season. Visitors are supposed

to queue up at designated spots and get on a light rail system, sort of

like the New York City subway. Unfortunately there is no money to

build the light rail system so the park service uses noisy diesel buses

instead. The buses aren't accessible to those in wheelchairs,

however, so people in wheelchairs have to plan their activities one day

ahead of time in order to reserve an accessible shuttle. Overall

the number of visitors and vehicles coming into the park has doubled

since 1970 while the facilities at the rim have not grown. Even in

the harsh cold of mid-October, for example, all the hotel rooms and most

of the campsites were booked. The park follows the river for

nearly 300 miles and the rim is deserted for most of this distance,

although from the air one can see a network of dirt roads that afford

vehicle access. If the Park Service picked a spot 30 miles to the

west and developed some new hotels, the experience of visiting the park

would get back to where it was in 1970. But it isn't going to

happen so unless you're strong enough to hike while carrying two gallons

or water per person per day the only way to get away from the crowds is

to go to a national park in Canada or to visit one of the less popular

U.S. national parks. Our favorites for a mix of scenery, comfort,

and lack of crowds are the following: Death Valley (complete with

golf course and below-sea-level airport), Grand Teton, any of the parks

in Alaska, and Big Bend.

Shopping on the road is delightful and frustrating at the same time. Delightful because there are so many beautiful chain stores all across America. Frustrating because with a 27' Winnebago it becomes impossible to accumulate. Shopping at Circuit City in Massachusetts is painful because anybody who actually knows anything about circuits can find a better job at a tech company. In a small city, however, Circuit City might be the best employer for 100 miles and the guy who installs car stereos can be a real craftsman. We became connoisseurs of the discount stores: Wal-Mart-ghetto/old; Target-overrated; Kmart-perfect. Mostly, however, we were astonished by the luxury and designer goods for sale all across the United States. In the old days rich people and merchants who served them lived in the big cultural capitals: New York, Chicago, San Francisco. A woman in New York would put on a designer dress and go to the Metropolitan Opera. Today you can buy that designer dress in the exurbs, right next to the Blockbuster movie rental shop that killed off the nearby movie theater. We spoke with one woman who was planning to buy an SUV with approximately the same price, size, and gas mileage as our Winnebago (and exactly the same engine). She wanted the extra room for her newborn boy and his appurtenances. What about a minivan, I suggested, because they have a lot more interior room than SUVs and use half as much gasoline. "Oh, I could never been seen in a minivan; that's so suburban," she replied in horror at the thought. Then it hit us: she lived in the suburbs, hard by an Interstate highway, she never went into the city except to work, she never attended cultural events. People in the cultural wasteland have always aspired to be like New Yorkers. In the 1950s they did it by forming great books clubs and cultural societies, by putting on theatrical productions. In a suburb of two-career households, however, nobody has time for these pursuits. So Americans have applied their checkbooks to the problem; if we can't all think like New Yorkers and be exposed to a lot of ideas then at least we can wear the same clothes and jewelry and be exposed to the same automobiles.

When one is plugged into the daily flow of news the current hot story of the day seems natural. The O.J. trial on the front page again? Why of course. When one drops out of telephone, radio, and television contact for a week at a time, however, the front page news is striking. From June through October 2002, every time we emerged from the wilderness we'd find George W. Bush complaining about Saddam and Iraq and every time we felt diminished. Iraq is a country that, before the Gulf War, had a GDP comparable to that of West Virginia. George W. Bush represented the entire American public. Was it possible that we the American People had nothing better to think about than a tiny country on the other side of the globe? It occurred to us that, as a matter of protocol, Queen Victoria would not have dealt directly with the potentate of an insignificant foreign land. It would have diminished the citizens of England to see their leader treating one-on-one with the leader of an inferior nation. A problem like Saddam would have been delegated to a 3rd undersecretary in the Foreign Office. When asked about Iraq, we kept expecting to hear George W. say "I'm not sure. I delegated that problem to Colonel Smith and he is going to report back to me in three months. Can we move on to questions that more directly concern our society?" But of course it never happened.

Our itinerary took us through the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi

Valley, California and it soon became clear that one reason Ronbo stands so much taller

than George W is that he had a better adversary. Ronald Reagan's enemy was

the Soviet Union, with its thousands of nuclear warheads and ballistic

missiles, tens of thousands of fighter jets and tanks, and 3.7 million

troops. Another difference is that George W. Bush talks about a "war" with

Iraq. The term "war" makes it sound as though there is some chance of

losing. Reagan did not have a "war" against Grenada; at the time the

government called it an "operation" and the press called it an "invasion".

Reagan did not have a "war" against Libya when he bombed Mu`ammar Qadhafi's

house and killed his 15-month-old daughter (along with a dozens of other

civilians); it was referred to as the "American bombing of Tripoli".

Our itinerary took us through the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi

Valley, California and it soon became clear that one reason Ronbo stands so much taller

than George W is that he had a better adversary. Ronald Reagan's enemy was

the Soviet Union, with its thousands of nuclear warheads and ballistic

missiles, tens of thousands of fighter jets and tanks, and 3.7 million

troops. Another difference is that George W. Bush talks about a "war" with

Iraq. The term "war" makes it sound as though there is some chance of

losing. Reagan did not have a "war" against Grenada; at the time the

government called it an "operation" and the press called it an "invasion".

Reagan did not have a "war" against Libya when he bombed Mu`ammar Qadhafi's

house and killed his 15-month-old daughter (along with a dozens of other

civilians); it was referred to as the "American bombing of Tripoli".

With a $1 billion per day peacetime military budget the cost to the American people of bombing Iraq versus not bombing Iraq is insignificant. It really isn't clear why American military action against Iraq should be news here in the U.S. It would be nice to think that Americans are concerned about Iraqis caught in the crossfire but that explanation seems to be contradicted by the fact that approximately one million people died in the Iran-Iraq war without generating significant news coverage here. Perhaps the proposed bombing is a fit subject for news because an attack on Iraq would make Arabs hate Americans. Against this theory is the fact that they already hate us enough to blow themselves up whenever there is a chance they can take some Americans with them to the grave (and if you watch CNN it seemed like practically the entire Arab population turned out to dance in the streets after the World Trade Center bombings); how much more could they hate us?

Actually the interesting question for political science is not why the U.S. is so bellicose but why we aren't more bellicose. Our military is now as powerful as the next 15 most powerful nations combined. When the Romans were in the same situation they kept conquering more and more territory even though historians can find no rational reason for the additional conquests. An increasingly far-flung empire in a world without trucks, airplanes, or telephones was not actually beneficial to the Romans. Ultimately many historians concluded that the Romans kept beating up their neighbors simply because they could, i.e., because they had such a large army and they couldn't figure out what else to do with it. Saudi Arabia is a good example of something that future historians will have a tough time explaining. Here is a country with a small population, a large amount of land, a weak military, and one-quarter of the world's oil. The average Saudi professes a profound hatred of Americans (only 12 percent of Saudis polled by the Arab American Institute had a favorable view of the United States) and backs up that hatred with liberal financial support of terrorist groups that like to kill Americans. Why didn't the Americans simply invade the country and nail up a sign saying "Welcome to the American Possession of Saudi Arabia", sell off the oil, and send every U.S. man, woman, and child a check for $80,000 (Saudi Arabia is estimated to have approximately 1 trillion barrels of easily accessible oil or 4,000 barrels per American citizen, worth about $30 per barrel once out of the ground). Obviously this would make some Saudis unhappy but the unhappiness of some locals doesn't stop the U.S. from holding on to Guam, Puerto Rico, Samoa, and the rest of its current possessions.

[One fears that a historian who looked into this question more closely would discover that the rulers of the United States find it more personally profitable to tax middle-class Americans to pay for a huge military, use that huge military to keep a small elite in power in Saudi Arabia, and then get contracts and investments from that elite. George W. Bush himself benefited from a Saudi sheikh's investment in Harken Energy and the company's subsequent award of an offshore drilling project in Bahrain.]

The saber-rattling over Iraq did provide some relief from an even more mournful topic...

At one point we listened to a lecture on the Roman Revolution, that period in

the 1st century BC when Rome went from being a republic to being ruled by

despots. At a critical point the smart politicians realized that it wasn't

necessary to be a skilled debater nor to be seen as right. The new-style

politician came into the Senate flanked by a group of armed thugs. The other

Senators would be intimidated into voting for the proposed legislation. "That's

just like the 2000 presidential election in Florida when George W. and his

brother were down there with a pack of lawyers!" we exclaimed. An even

more familiar part of the lecture was that during the Roman Revolution the

wealthy grew enormously wealthier while the masses stagnated economically. Much

of this new wealth went into spectacularly large and opulent houses within Rome

and even larger and more opulent vacation houses in the countryside. We

reflected on the fact that there were new $2 million houses being offered for

sale in nearly every city we'd visited, despite the fact that most of these

cities had stagnant economies with few decent jobs outside of the local

hospitals or government.

At one point we listened to a lecture on the Roman Revolution, that period in

the 1st century BC when Rome went from being a republic to being ruled by

despots. At a critical point the smart politicians realized that it wasn't

necessary to be a skilled debater nor to be seen as right. The new-style

politician came into the Senate flanked by a group of armed thugs. The other

Senators would be intimidated into voting for the proposed legislation. "That's

just like the 2000 presidential election in Florida when George W. and his

brother were down there with a pack of lawyers!" we exclaimed. An even

more familiar part of the lecture was that during the Roman Revolution the

wealthy grew enormously wealthier while the masses stagnated economically. Much

of this new wealth went into spectacularly large and opulent houses within Rome

and even larger and more opulent vacation houses in the countryside. We

reflected on the fact that there were new $2 million houses being offered for

sale in nearly every city we'd visited, despite the fact that most of these

cities had stagnant economies with few decent jobs outside of the local

hospitals or government.The richest 1 percent of families in our country now have as much income as the bottom 40 percent of Americans. [Paul Krugman again; NYT; http://www.pkarchive.org/economy/ForRicher.html] That's sort of an abstract concept until you realize that it means that those families can afford to employ 100 million Americans, at their present salaries, as serfs on their estates. And indeed serfdom is a familiar part of the landscape. You can't see it in Manhattan where the rich spend most of their time and money indoors, hidden behind elevators and curtains. But you can sure see it in California: the $20 million Napa Valley estate might be right next to a main road. Migrant Mexicans pick grapes in the front; a $1 million turbine-powered helicopter sits in the driveway in back, ready to take the owner to his one of his six other $20 million residences. Up and down the Pacific coast we visited harbors where $100 million sailboats sat idle with their crew of 8, waiting for the owner to come in via Gulfstream jet to spend a few nights entertaining friends. Alex's irresistibility earned us a tour of the 171-foot Georgia, the world's biggest single-mast private yacht at the time of its construction. The 200'-high mast had a red beacon on top to warn airplanes. We'd never heard of the owner, John A. Williams, a big winner in the 20th century American real estate lottery, but thought that maybe one day our kid could be his grandchild's serf (if Mr. Williams should die after January 1, 2010, his descendants will pay no estate tax and the Williams dynasty will continue undiminished).

You'd think the events of 2002 would have left the working class dispirited, especially the young. Interest rates went down, which might have made buying a house more affordable except that prices immediately rose to the point that monthly payments were the same as before. The only effect of the low interest rates was to enrich people who already owned property. Corporations laid off workers because they didn't have a cash cushion. Where was the cash that they might have salted away during the boom times? Taken home by the top managers. A good example was Disney where top management took home nearly $2 billion during the 1990s. Today, after a string of lackluster movies and a tough market for its resorts, the company has $1.24 billion in cash, barely more than they paid their CEO since 1995. This led the management to conclude that "making movies in Los Angeles is too expensive" so they closed an 80-year-old animation studio in Burbank and sent all the jobs to Eastern Europe and Australia. If corporate criminals eviscerating workers' retirement savings wasn't bad enough, 2002 was also a year in which George W. Bush sent their children to risk their lives in miserable foreign countries so that he and his cronies can continue in the oil business as usual.

Why do they go on? Why do they go on working? Why do a remarkable number vote for the Republican Party?

My personal theory on so few people drop out of the workforce is that the consequences are simply too dire. If you drop out in Canada or Europe you still get health care. In the U.S. we spend roughly 13.5% of GDP on health care, which gives us the most expensive health care system in the world, far more expensive than the really good universal health care systems in Germany (10.5%), France, or Canada (both around 9.5%). In the US if you're truly useless to the economy you get free healthcare: the old get Medicare and the poor with kids get Medicaid, to the total tune of $418 billion in FY 2003. However, people who can still contribute to the GDP must take that $9/hour job at Starbucks in order to get health care or the $7/hour job processing chicken carcasses in order to buy food. Housing is another issue. The Federal Government's Millennial Housing Commission concluded that the poorest 20% of Americans paid 76% of their income in rent in 1999, up from 69% in 1985. For wealthier Americans who are able to buy homes and deduct the interest payments, the report notes that "by far the biggest government demand-side subsidy continues to be the tax advantages bestowed upon upper-income owner-occupied housing. ... As measured by lost tax revenues, this demand subsidy has grown an inflation-adjusted 90 percent between 1985 and 1999, according to IRS statistics." (Source: http://www.mhc.gov/.)

Why do so many poor people vote for the Republican Party? We didn't find anyone between Boston and Alaska who felt that he or she had any personal influence over politics. Even the richest airplane owners that we met felt that they weren't wealthy enough to buy time with a national politician. Working class people assumed that politicians of both major parties were owned by the rich and that therefore any new government programs would be paid for by new taxes on people of modest means. They vote for Republicans because they hope that there will be fewer new government programs.

Every day we'd read a newspaper article about how telephone companies

have overspent on infrastructure. Yet we managed to drive 7000 miles

while our cell phones (Voicestream/T-Mobile and Sprint) reported "no

service". When the phones finally found service on the crowded coast

of California, half the calls were dropped. Internet connectivity

when mobile was an impossibility and, because there isn't any

infrastructure there really aren't any useful Internet applications

for mobile users. With the cost of an 802.11 base station down below

$100 we found a couple of sandwich shops that had spread free

connectivity over their premises for customer convenience. But at

chain stores, hotels, campgrounds, and government facilities, you

could forget it.

Every day we'd read a newspaper article about how telephone companies

have overspent on infrastructure. Yet we managed to drive 7000 miles

while our cell phones (Voicestream/T-Mobile and Sprint) reported "no

service". When the phones finally found service on the crowded coast

of California, half the calls were dropped. Internet connectivity

when mobile was an impossibility and, because there isn't any

infrastructure there really aren't any useful Internet applications

for mobile users. With the cost of an 802.11 base station down below

$100 we found a couple of sandwich shops that had spread free

connectivity over their premises for customer convenience. But at

chain stores, hotels, campgrounds, and government facilities, you

could forget it.

In the 1990s the Internet was expected to become an exciting tool for the rich. Investors poured money into Internet applications and hippie malcontents fretted about a "digital divide". But it turned out that the rich don't need Internet. If Joe Moneybags has a question he asked one of his assistants, not Google. If Joe Moneybags wants to find out what France is like he has the company Gulfstream drop him off in Paris. If Joe Moneybags wants to interact with friends on the West Coast, he has the corporate jet fleet pick everyone up for a weekend at his ranch near Jackson Hole. With PCs costing less than $500 and cable modem service available in smaller cities for $20 per month, the Internet turned out to be boon for the lower middle class. They can't afford a European vacation but they enjoy interacting with Europeans who share their interests. They can't afford to visit their friends in distant cities but instant messaging is free. Thus did Internet join the ranks of other things that are consumed primarily by the lower middle class, i.e., not especially attractive to investors.

Collapse of interest in the commercial world is typically followed up by a collapse in interest by government and non-profit organizations and Internet has proved no exception. Here in Boston we're spending nearly $15 billion on a new downtown highway but not one penny on information systems that might make it unnecessary for people to get into their cars. People drive home to read their email because there isn't a public wireless Internet network in Boston ($100 per node). People drive around in circles, clogging the roads and polluting the air, because they can't connect to a public wireless network to get directions from maps.yahoo.com. People drive to work by themselves in a 7-passenger SUV because, well, some of them because they can but others because there isn't a system that would say "you're about to drive right by someone who is ready to leave now and who works in the same office building as you and whose presence in your vehicle would enable you to use the carpool lane". People get in their cars because there is no easy way to use one's cell phone to figure out that there is a nearby bus that is about to arrive at the stop and is going to one's destination.

Out west the situation is even worse. Governments there spend $billions each year on public transit. The nicest public transit buses in the U.S. are on the Pacific coast and one reason that the interiors stay pristine is that nobody rides them. Transportation economists concluded decades ago that fixed-route public transit systems would never work in the American West because the population density was too low. Their alternative proposal was a system of shuttle vans coordinated by a staff of telephone operators and radio links. You'd call from Point A, say that you wanted to go to Point B, and the nearest van that was heading in that direction would come pick you up, sort of like the SuperShuttle services that are so popular at airports. The economic feasibility of such a system was demonstrated in the early 1970s in Regina, Saskatchewan and exists today in Bellingham, Washington (http://www.ridewta.com/dialaride.html; 50 cents per trip to connect to the main routes). In an age of wireless data transmission, GPS, and people walking around with cell phones that have full keyboards and can browse Web pages it should be possible to build a much better service than what economists envisioned in the 1960s. This would work especially well in a place such as Napa Valley where all the trips are essentially either north and south and very few homes or businesses are more than 1/2 mile from the main north-south highway (subject to massive traffic jams currently and home to some gleaming new buses, all of which are empty because they don't make short detours to pick people up). But although we bought the local newspaper in every town through which we traveled, we never read any discussion of the idea, only debates about how many more $billions to sink into new rail and fixed-route bus systems.

In the world of aviation the lack of interest in information systems has less expensive consequences in terms of economic costs but results in much more dramatic news stories. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) does not publish on the Internet electronic versions of the charts that are necessary for navigating in an airplane. Nor does the FAA publish a terrain database. Consequently the moderately priced avionics in a small airplane generally lack the ability to download such information even if one wanted to pay for it from the commercial suppliers to the airlines. The result? Pilots flying at night in brand-new $250,000 airplanes smash into mountainsides because they didn't get any warning that they were flying near the terrain (mountainsides are typically unsuitable for building houses and therefore very dark at night). When George W. Bush is giving a talk at a high school in Alabama it becomes temporarily illegal to fly anywhere near that high school and this is reflected in an FAA Temporary Flight Restriction (TFR). TFRs are also issued around sports stadiums during games, around gas tanks and oil storage facilities, and anywhere else that the FAA thinks a young Jihadi might like to fly. If you call for a preflight briefing you might hear about one as "A 5 nautical mile radius at 20 miles out on the 317-degree radial of the Boston VOR [a navigation beacon], 3000' and below". Ever since September 11, 2001, the government has been scrambling fighter jets after Cessnas, interrogating pilots after they land, revoking pilots' licenses, issuing more TFRs, and complaining that people are violating them. Nobody in either the FAA or the Airline Owners and Pilots Association has ever said "Hey, since the FAA operates the world's largest network of radios and just about every airplane flying right now has a moving-map GPS receiver, maybe the FAA should promulgate a data transmission specification and transmit TFRs directly to the airplane so that the GPS can start beeping when the pilot gets close to a TFR."

Sometimes the technological stagnation of the United States takes on a human face. In the October 2002 issue of WIRED magazine it was John Payne, the Chief Information Officer of San Francisco Airport (SFO). Payne estimated that wireless Internet connectivity could be spread over the airport for $750,000, "a pittance compared with the billions that SFO recently spent on a new international terminal." But he's not going to do it until he can find a way to charge each user $10 per day (10 times the cost of cable modem Internet service or DSL to a typical home). Payne expects that it will be many years before he can find the right combination of partner and fee structure but he is in no hurry.